What is a Sketch?

A sketch can be anything from modifying a lead sheet, to a condensed version of every note that will appear in your arrangement. In my arranging process I tend to use both, and that's what I'll be sharing with you. However, for clarification's sake, we will refer to the latter, more detailed sketch as "the sketch".

Many people are resistant to the idea of sketching, and prefer to attack the full score from the beginning, something that I do from time to time (especially with a time crunch). Though I think it is valuable to take a step back and evaluate your choices in the purest form—what section goes where, and what material will be included within each section.

If you've never written a sketch before, I promise that it will be helpful, especially if you're an experienced arranger. When I started arranging, I never wrote a sketch. Once I integrated sketching into my process, the clarity of my arranging and compositional ideas increased, and (as noted above) that clarity is what allows me to write without a sketch today when required. Breaking arranging techniques down to their most fundamental forms is one of the most effective ways to improve your clarity of intent in your arrangements.

In addition, I prefer to sketch from beginning to end, at all parts of the process. Some choose to sketch a section, then orchestrate it, and continue that way. This is a perfectly valid method, but I've found I personally have better control of the energy and content of an arrangement when I sketch all of my ideas prior to orchestration.

Here's a glimpse into my sketch process, from beginning to end:

Write my own lead sheet with the melody and original chord progression

Create a form chart (see "The Form")

Write another lead sheet, this time including all parts included in my form chart, and make any reharmonization decisions throughout the arrangement; my "Arranger's Lead Sheet".

Begin sketching accompaniment material in a full sketch (see "Writing a Sketch")

Ready for Orchestration!

The Form

Once you've decided what song to arrange (or it has been decided for you), the first step is to decipher the form of the original song. If it's from the Great American Songbook tradition, it's likely that it falls into a "traditional" song form: AABA, Blues, ABAC, etc. If it's a more contemporary song, it could look more like: Intro, Verse 1, Pre Chorus 1, Chorus 1, Verse 2, Pre Chorus 2, Chorus 2, Bridge, Chorus 3 (double), Ending.

Once I've figured that out, I decide how I'd like to lay out my arrangement. If I'm arranging a "standard", it might look something like this:

Intro, Chorus (AABA), Solo Chorus (AABA), Interlude, Chorus (AABA), Ending.

If it's a pop song, I could choose to follow the original form. For our hypothetical pop song example, it would look like this:

Intro, Verse 1, Pre Chorus 1, Chorus 1, Verse 2, Pre Chorus 2, Chorus 2, Bridge, Chorus 3 (double), Ending.

At this point, with the pop song example, I might examine whether changes to the original form might make it more compelling for the particular situation. This is up to the arranger, and is informed by personal taste and the given performance situation of the arrangement.

I formalize this in what many call a Form Chart. Typically this is just listed on a piece of paper, and used for reference when writing my "Arranger's Lead Sheet".

The Tune

Once I've picked a tune (or been assigned one by commission), and I've finished my informal form chart, I transcribe the tune from a popular recording. With jazz standards, I typically turn to the most popular recording, or when there are many popular recordings I fall back on vocal performances, often by singers like Frank Sinatra or Ella Fitzgerald. They both tend to deliver the melody with a clear-cut and well received interpretation, and their arrangements typically include the original (or accepted) harmonization. This is the "Lead Sheet"m from which I work.

Once I've written the lead sheet, I map out my form chart, including the melody and harmony, and decide if there are any alterations that I would like to make to the tune to bring a fresh perspective. The extent that I make alterations is determined by many factors. If I am writing an arrangement for my own groups, I make whatever musical decisions I think most represent my voice. These changes are often radical given my particular taste. Though, if I am commissioned to write an arrangement, I listen to previous arrangements that the group has commissioned, and use that to inform my taste. If writing an arrangement for an artist who wrote the song, particularly in a pop context, I keep the changes to a minimum, only providing color when necessary for the energy level. This new lead sheet, running from beginning to end of what will become my final arrangement, is my arranger's lead sheet.

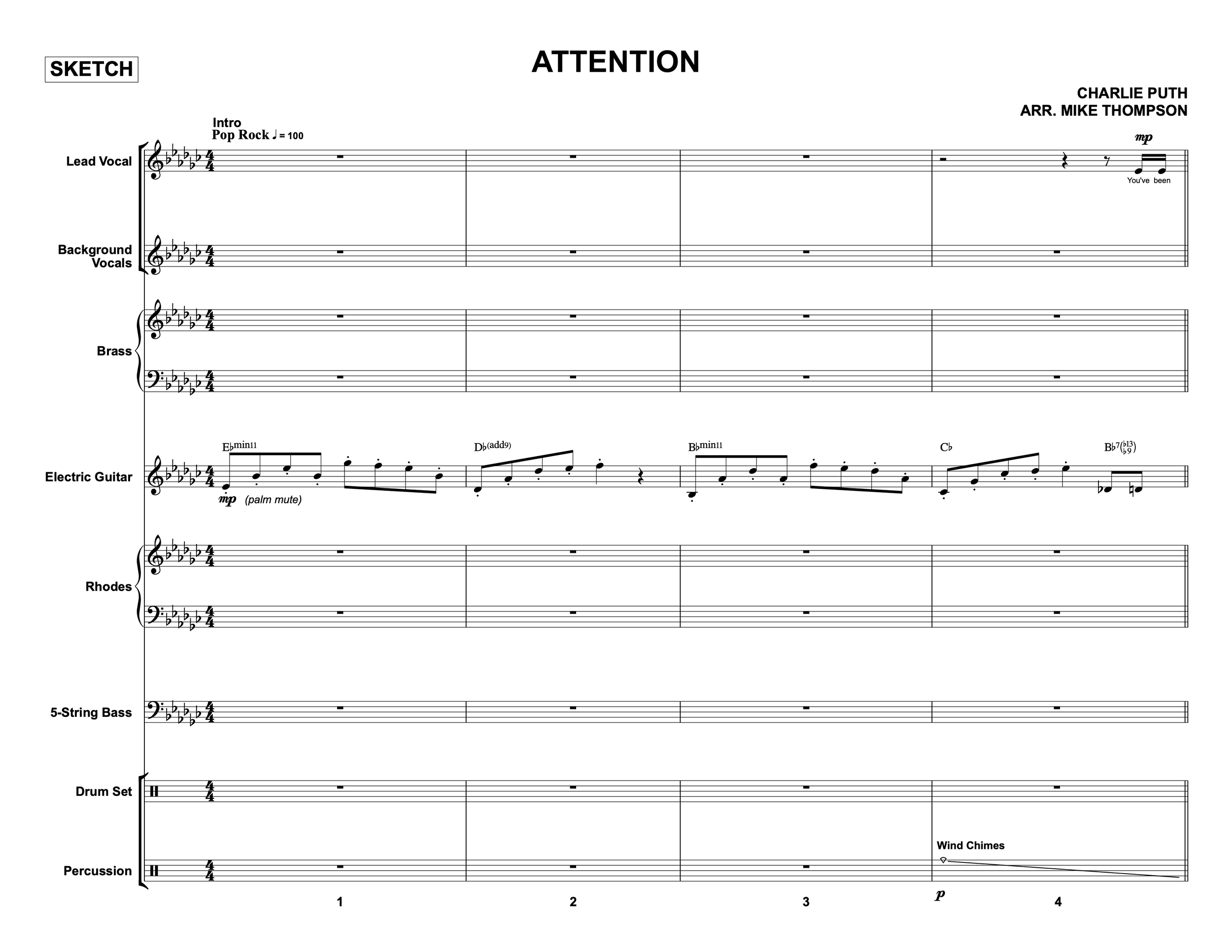

Writing a Sketch

Given that I've written my arranger's lead sheet, I now know what the melody and harmony will be for the arrangement. Now it's time to write the full sketch. This can look radically different for different arranging projects, but I'll provide some examples of my own sketches in different scenarios.

Pop Sketches

If writing for a pop group, I might only sketch three or four lines: the melody, accompaniment, bass line, and basic drum grooves. If the pop project includes a string section and/or horns, I'll include a grand staff for each.

Orchestra

All of my orchestra sketches look really similar. They typically include a grand staff for each major section of the orchestra, with additions for percussion: Strings, Woodwinds, Brass, etc. If the project include a vocalist, I'll include that as well.

Big Band – Traditional

For a "standard" interpretation for big band, I'll include a grand staff for each section: Saxes and Brass, and individual staves for the rhythm section.

Big Band – Contemporary Large Ensemble

If writing in the contemporary large ensemble style, I will often choose to use simply a grand staff or 3 staves: one for the primary melodic material, one for contrapuntal or accompaniment material, and one for a bass line. Sometimes these can be combined into two staves (melody and accompaniment, then bass line, or melody, then accompaniment and bass line), but it is often useful to separate them into three.

Considerations

Throughout this process, it's important not to get too committed to what you've written in your sketch. Editing happens throughout the whole process, and you can change any part of the arrangement until you record it (or submit it to a group, at least). It might be useful to return to the sketch when those changes to be made, but it's certainly not necessary. These are not rules, simply advice.